Sanctuary city under attack

chronicles the attack on San Francisco's status as a sanctuary city for immigrants--and the struggle to stop that attack.

SAN FRANCISCO is often described as a progressive city. Its residents have taken stands for same-sex marriage, against the war on Iraq, and for the rights of immigrants.

The city started the year, for example, putting up multilingual posters around town informing immigrant residents that they are welcome here, and cannot be denied access to services. In 1989, San Francisco passed the Sanctuary Ordinance, making it a "City and County of Refuge" for all immigrants.

Today its "City of Refuge" status is under attack, and the word "sanctuary" (which means "a place of safety") is being redefined in very narrow terms. The attack is being waged by a spectrum of anti-immigrant forces--from the racist Minutemen, to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), to the mayor.

ICE launched a high-profile raid on the El Balazo Taqueria chain on May 2--on the heels of May Day marches for immigrant and worker rights. This raid was part of a nationwide campaign of repression on the part of ICE and marked the beginning of stepped-up attacks in San Francisco in particular.

ICE vans have since been seen patrolling local neighborhoods and harassing Latino drivers. On July 30, the same day that over 200 pro-immigrant supporters came out to counterprotest an anti-immigrant Minutemen rally, ICE conducted yet another raid in the predominantly Latino Mission District.

Though no one was arrested, ICE agents handcuffed, held and interrogated up to 17 people in the early-morning raid. After subjecting two entire immigrant families to this treatment for nearly three hours, the agents left--and took with them documentation papers, cell phones and other personal effects. They left behind a sense of fear, violation and anger.

San Francisco's history as a sanctuary city is over 20 years old, dating back to 1985, when it granted refuge to immigrants from El Salvador and Guatemala. Four years later, the Sanctuary Ordinance extended the policy to all immigrants. As the city government Web site, sfgov.org states:

The [Sanctuary] Ordinance is rooted in the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s, when churches across the country provided refuge to Central Americans fleeing civil wars in their countries. In providing such assistance, faith communities were responding to the difficulties immigrants faced in obtaining refugee status from the U.S. government. Municipalities across the country followed suit by adopting sanctuary ordinances.

In short, sanctuary status was a gain won through struggle. In 2006, when the immigrant rights movement re-emerged across the U.S., San Francisco saw a series of demonstrations culminating in a May Day march of 200,000 people. The May 1 marches that followed in 2007 and 2008 were smaller, but the fact that they happened here and in other cities has helped re-establish the International Workers' Day tradition.

In February 2007, Democratic Mayor Gavin Newsom "reaffirmed San Francisco's commitment to immigrant communities" in an executive order. Yet since July 2008, Newsom has handed over no less than 38 immigrant youths who were being held in the Juvenile Probation Department to ICE. Newsom now claims that nothing in the Sanctuary Ordinance allows for the city to "shield convicted felons"--the youths were being held on drug-related charges--but the fact is that his actions reverse nearly two decades of tradition here.

MOST RECENTLY, a young immigrant man from El Salvador has been accused of a triple homicide. Edwin Ramos, age 21, has been labeled a gang member and is alleged to be here in the U.S. without documentation. His lawyer says that all three allegations are untrue.

It should be pointed out that, at the time of writing this article, not one of the allegations against Ramos has been proven. This detail is ignored by the likes of Republican Rep. Tom Tancredo of Colorado, who has built a career on bashing immigrants. Tancredo has suggested that the U.S. Department of Justice should take over the case from San Francisco. "Because San Francisco's political leaders have already demonstrated their willingness to act in flagrant violation of federal law, I do not believe that local judicial institutions can be trusted to fairly try the case or mete out an appropriate punishment."

Diana Hull, president of Californians for Population Stabilization, an anti-immigrant group that claims it is "preserving a good quality of life for all Californians," went a step further--condemning all sanctuary city policies. "We need to remember always that a death-dealing policy like 'sanctuary' hides behind the false mantle of compassion," Hull said.

What Tancredo, Hull and the Minutemen share is a racist, anti-immigrant agenda and see the Ramos case as an opening to promote their vile politics. The "gang-related" rhetoric surrounding the case is a further attempt to demonize Ramos, sanctuary status and immigrants in general by tapping into the "tough-on-crime" (read "racist and anti-poor") rhetoric that so many politicians already use. It also dovetails with the practice of referring to undocumented immigrants as "criminals" and "illegals."

Whether or not Ramos is found to be guilty of murder, and whatever his actual documentation status, the movement must stand united around a simple demand, "ICE stay out of SF!" If we say its okay for ICE to come in and take some folks away, then ultimately we make it easier for them to take everyone away. Give ICE an inch, and they will try to take a mile.

Why does Newsom seem ready to open San Francisco to ICE and throw sanctuary city status away? In the same week that he began turning over inmates from Juvenile Hall to ICE, Newsom publicly floated the idea of running for governor in 2010. In moving to the right, and away from his earlier "commitment" to immigrant communities, Newsom is attempting to better position himself within the workings of the Democratic Party establishment.

Republicans like Sen. James Sensenbrenner have authored some of the worst bills to come before Congress in the name of "immigration reform," but we should all keep in mind that the Democrats' performance has been less than inspiring. Now, with Barack Obama poised to be elected in November, many in the immigrant rights movement are hopeful that he will deliver some changes.

Given the needs of big business for a stable and low-paid workforce, it is almost certain that the next president will bring changes in U.S. immigration policy. But will they be the kind of changes that those fighting for equal rights actually want? Thus far, Obama's stance on immigration issues has been a mixed bag at best.

Having once promised to never vote for increased militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, he did just that as a senator last year. Obama has announced an intention to grant driver's licenses to undocumented immigrants (which we would welcome) but has also repeatedly staked out positions that John McCain could be happy with--fines, English-speaking requirements and "back of the line" penalties for those seeking permanent residence in the U.S.

This is the context of Newsom's shift to the right.

Additionally, California is facing a huge budget crisis, and Newsom is no doubt trying to scapegoat and cut corners--by robbing those in need. By pointing the finger at undocumented immigrant youth, Newsom has opened the door to the Minutemen and others who see a chance to make headway against a high-profile sanctuary city like San Francisco.

FORTUNATELY, THESE attacks aren't going unchallenged. Though the movement has seen its ups and downs, the huge spike of activity in Spring 2006 breathed new life into the local and national movement. Only three days after the El Balazo raids, 250 people came out to protest in the middle of a Monday at ICE headquarters. An organizing meeting soon after brought together 40 or so activists to strategize about next steps. That meeting put some forces in motion, working in loose collaboration, to respond to the raids and other attacks.

The El Balazo Workers Defense Committee was established by activists and workers from El Balazo Taqueria to build a campaign around their case, and a defense fund was created to help deal with the hardships that many of the workers and their families now face. The first fundraiser drew over 120 people and raised thousands of dollars. Another fundraiser is scheduled for the end of the month.

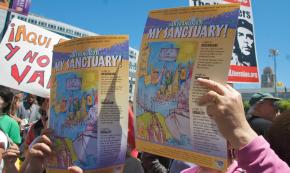

Know-your-rights forums are being organized, and a "Regional Town Hall Meeting to Stop the Raids" is set for early September in Richmond. And that is just the beginning. In San Francisco on July 29, about 100 people came out to protest Newsom's attacks on our sanctuary status. The next day, over 200 came out on short notice to protest the Minutemen.

At that rally, many people got their first news of the raid that had happened in the Mission District that morning, and an emergency meeting was called for that same evening. That meeting brought together another 35 people or so to discuss what had happened, and what to do about it.

These are important steps toward building the kind of movement necessary to stop the raids and defend the Sanctuary Ordinance. While Mayor Newsom is pushing hard and fast, there are several members of the Board of Supervisors who have voiced opposition to what he is doing. What is needed now is increased coordination between the forces in the local pro-immigrant rights movement.

We need to come together to defend our communities but also to define "sanctuary" on our terms. A successful strategy would include a variety of means, including a legal strategy for the courts and collaboration with city supervisors who are already leaning in our direction.

But the bedrock of any strategy must be grassroots organizing and mass action. The powerful experience of May Day 2006 has not been forgotten, and rallies and meetings since then have shown that many people are willing to organize and fight for dignity, equality and justice. Our movement will need to continue to tap into that dedication and strength, and to cultivate it in more and more people.

What we do to turn the tide here will be a component in building a strong national movement strong enough to push the direction of future immigration law reforms. And that is something we will definitely need, whoever becomes the next governor of California or U.S. president.